We discuss snub-nose .38 revolvers and why they still make sense for concealed carry today.

“I gotta go to the bathroom.”

“You gotta go, you gotta go.”

So began one of the most iconic scenes in mobster movie history, as Michael Corleone heads to the men’s room, to retrieve a hidden handgun to murder his father’s would-be assassin. The gun? A Smith & Wesson snub-nose revolver, chambered in .38 Special. When you think of the great detective movies, mafia movies and all of the books and documentaries of that era, the snub-nose .38 Special makes a constant appearance.

What is it about that particular handgun and cartridge combination that’s so iconic?

One would think that in a world of lightweight, striker-fired autoloading handguns—with their double-stacked magazines and tritium night sights—the short-barreled revolvers would have long ago gone the way of the dodo. But that’s not the case, for a number of good reasons. In fact, for many shooters, the snub-nose .38 Special makes a whole ton of sense.

Dating back to the late 1920s—where the Colt Detective Special made its debut—the snub-nose revolver is easily concealed, making it a perfect choice for the off-duty police officer or plain-clothes police detective. Likewise, it makes a sound choice for those with a concealed carry permit who want the ability to defend themselves in a close-quarters situation.

Oddly, the snub-nose revolver I carry is the same make and model that my father carries (though I didn’t know it at the time I bought it), and the same gun my grandfather carried: a Smith & Wesson Model 36, five-shot .38 Special. You might recognize it as the gun Al Pacino (as Michael Corleone) used in the scene I mentioned earlier. Though many will view it as simply a “belly gun,” the snub-nosed .38 Special is so much more than that.

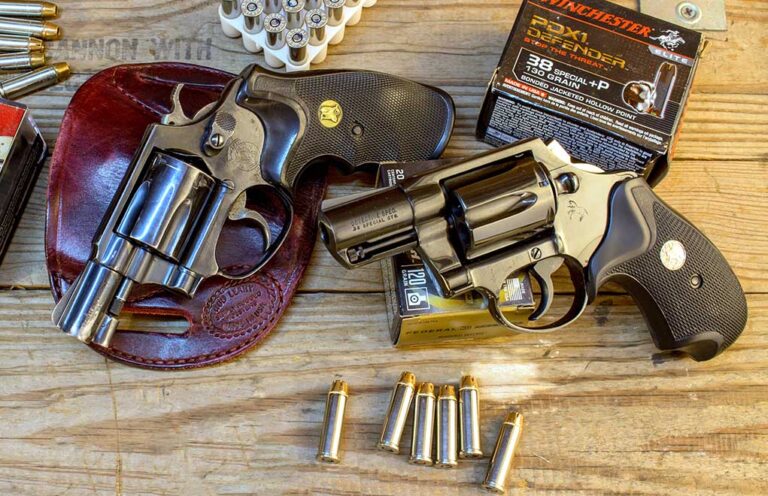

Snub-Nose .38 Revolvers

Most of the snub-nose .38s have five-shot cylinders, though you’ll come across some six-shot models. Either way, I’ve heard folks insist that the lack of cartridge capacity makes these types of firearms nearly obsolete, yet I completely disagree. As we’re talking about a defensive gun, five shots should get you to a safe situation, or at least give you time to reload the gun. Statistics have proven this.

I get the wisdom of a double-stack magazine, but I’ll also say that a five-shot revolver certainly has the ability to stop a threat. In a law enforcement role it might not have the capacity to sustain a prolonged firefight, but as a civilian who just wants to get out of a terrible situation—stop the threat—I don’t have a problem with my five-shot gun.

A double-action revolver is a unique design, which I view as two handguns in one. When the hammer is cocked, and the gun is fired in single-action mode, precision shots aren’t out of the question, even with a short barrel. Sitting at the bench with my S&W Model 36, I’ve been amazed at the group sizes printed by a 1⅞-inch barrel; switching to double-action mode and the heavier trigger pull will certainly affect the group size, but it’s more than acceptable.

I grabbed my trigger pull gauge to measure the difference in my S&W: In single-action mode, the trigger breaks consistently at 1 pound, 15 ounces, yet in double-action mode it ranged from 7 pounds, 12 ounces to 8 pounds, 8 ounces. Assuredly that increase in trigger pull requires a unique skill set, especially when firing a double-action handgun under pressure … but that’s part of the territory.

What I like about a revolver is the simplicity of the design. Yes, it requires some maintenance and you can get into trouble if the projectiles aren’t crimped heavily into the cartridge case, but generally speaking, a revolver tends to be much less finicky and much more reliable than the autoloaders. They have no problem feeding any kind of ammunition, simply because they don’t feed ammunition—you do. They don’t have an issue ejecting spent cases, because you do that. And they don’t leave spent cases all over the place, as they stay in the cylinder until you decide it’s time to remove them.

My Model 36 measures 1.32 inches at the widest point—the cylinder—and is rather easy to conceal, though the frame measures 0.53 inch and the grips widening to 1.15 inches at the swell. Though other popular autoloaders might measure right around an inch at the widest point, their outline is a bit squarer and blockier and can “print” a bit more than will one of the Colt Detective models or a Smith & Wesson J-Frame.

Depending on the grip, these snub-nosed .38 Specials can be easily carried in a shoulder holster, IWB holster or in one of the many OWB holsters; I carry mine in a Simply Rugged OWB leather holster, which is strong, comfortable and reliable.

Speaking of grips, my dad’s Model 36 sports the original square-butt J-Frame grips, yet mine have a set of (seemingly) oversized Pachmayr rubber grips, which came on the gun when I bought it used. Having spent a considerable amount of time with both guns, experimenting with both factory-loaded ammo and handloaded ammunition, I find the large Pachmayr grips well worth both the investment of about $35 as well as the additional footprint when carrying concealed.

Those J-Frame grips feel much too small in my hands—I’ve got long, thin fingers—and the grip angle feels all wrong in comparison to the Pachmayr’s. The pinky of my right (strong) hand tends to ride underneath the base of the traditional J-Frame grips, whereas I can get a solid grip on those Pachmayr rubber grips—and the targets show the difference.

Whichever model you choose, the smaller frame and shorter barrel need to be aimed properly, and if you feel a change in grips will help you get on target better, I see no reason not to pursue that avenue.

.38 Special Ammunition

The .38 Smith & Wesson Special came to light as an improvement over the .38 Long Colt. Released in 1898, the rimmed, straight-walled cartridge gave unprecedented velocities for the end of the 19th century. Using a bullet diameter of 0.357 inch—the “.38” name was a carryover from the heeled-bullet designs in the Short Colt cases that were fashioned to operate in the .36-caliber cap-and-ball conversion guns—the .38 Smith & Wesson Special has a case length of 1.155 inches, and a maximum cartridge overall length of 1.550 inches. Bullet weights generally range from 90 to 158 grains, with plenty of choices in between; I prefer bullets on the heavier end of the spectrum.

Looking at the advertised velocities for .38 Special ammunition, I’ve found that my 1⅞-inch barrel will measure anywhere from 65- to 110-fps slower than the test barrels, which are usually a 4-inch barrel. That velocity drop is to be expected in a shorter barrel, but I don’t find it to be an issue. With the wide range of factory ammunition available for the .38 Special, the cartridge becomes a chameleon.

With a good number of lower-velocity loads, which are fantastic for training, practice and even for carry for those who are recoil sensitive, the good old .38 remains a reliable choice; when you look at the +P—read: higher pressure and velocity—loads, it’s a different animal altogether. Couple that with the impressive advancements in handgun bullet technology, and the cartridge that was released during the McKinley administration takes on a whole new guise.

In the defensive handgun world, we often get hung up on numbers and statistics, using those little facts to attack and/or defend a particular cartridge. Let’s get this out of the way: The .38 Special isn’t the .357 Magnum, the .44 Magnum or the .45 ACP, no matter how many +s and Ps there are in the designation. But, it’s still a respectable blend of bullet weight, penetration and tolerable recoil.

With the majority of modern loads offering at least 10 inches of penetration in ballistic gel tests, even the reduced velocities generated by the short-barreled revolvers can stop a threat … if properly placed. Bullet construction will definitely play a role in the penetration, as a fast-expanding lead hollow-point will generally not penetrate as deep as a bonded core bullet, or as a non-expanding FMJ. But, I feel the .38 Special is “enough gun” to get the job done.

The standard .38 Special loads will feature bullets between 130 and 158 grains, at a muzzle velocity of somewhere between 770 fps and 850 fps, but expect a drop off if you’re using a 2-inch barrel. I like the American Eagle 158 FMJ at 770 fps for practice and plinking, Hornady’s Custom ammo line has their 158-grain XTP bullet at 800 fps, Buffalo Bore’s 158-grain gas-checked SWC at 850 fps, and HSM’s Cowboy Action 158-grain FN bullet at 840 fps.

For the recoil sensitive, or for those who want the minimal amount of muzzle jump and/or the ability to get back on target as quickly as possible for a follow-up shot, Federal’s Low Recoil ammo uses a 110-grain Hydra-Shok bullet at 980 fps, and Hornady’s Critical Defense Lite 90-grain FTX at 1,200 fps—though my gun clocked 1,040 fps with that load.

Punching With The +P

The +P loads increase both pressures and velocities and take the .38 Special into a new realm. Speer makes a load specially engineered for the snubbies, and their Gold Dot Short Barrel ammo uses the 135-grain bonded-core Gold Dot bullet at a muzzle velocity of 860 fps; I really like the way this bullet performs.

Federal’s Personal Defense Micro ammo line uses a flush-mounted HST bullet at 890 fps (expect lower in a snubby), and that might be my favorite handgun bullet for defensive purposes. Federal’s +P Punch line uses a 120-grain jacketed hollow-point at 1,000 fps, and their Personal Defense line offers a 130-grain Hydra-Shok Deep at 900 fps. Winchester’s PDX Defender +P load is built around a 130-grain bonded-core hollow-point moving at an advertised 950 fps, giving a sound blend of expansion and penetration.

The concerns over firing +P loads in a vintage handgun—say from the early 20th century where the metallurgy and construction wasn’t what we have today—are a real thing, but I’ve fired a whole bunch in my S&W from the early 1980s without issue. Take care with yours and seek advice from a gunsmith if you’re unsure.

Because of the age of the cartridge and the firearms produced for it early on, the .38 Special is much like the 7×57 Mauser and the .45-70 Government in that there seems to be two separate iterations of the same cartridge. If you have a modern handgun, you can take full advantage of both the traditional loads and the +P loads, though I’ll advise you to avoid firing too many of those +P loads from the short-barreled guns without hearing protection; they can flatten your eardrums.

Handloading for the .38 Special is a simple affair, as a pound of TiteGroup or Unique will give over 1,000 shots, and you can easily pour some wadcutters for practice, or gas-checked bullets for daily carry (my dad still likes cast lead bullets in his S&W revolver). The case uses a small pistol primer, and make sure you put a good crimp on your bullet to prevent them from pulling out of the case under recoil and jamming up your cylinder.

The Choice

I chose the .38 Special because it has that wide selection of ammunition choices, is easily concealed and is a pleasure to shoot. Its recoil is much less than that of the .357 Magnum or the .44s, yet it surpasses the .32s in bullet weight, if not in speed. While the results of the 1986 Miami shootout did show the cartridge’s shortcomings at longer ranges, I rely on my .38 Special for personal defensive purposes, the vast majority of which are conducted at ranges inside of 10 yards.

It is affordable—in both factory ammunition and handloaded stuff—to practice with, and in spite of my snubby having a sighting radius of just 3½ inches, it shoots surprisingly well. It’s been relied upon since the 1920s, and I wouldn’t be surprised if folks were still carrying a snub-nose .38 a century from now.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2022 Everyday Carry special issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More On Revolvers:

Read the full article here